On November 26th, we hosted our 13th Frontier Dialogue titled "Assessing the Impact of AI on Work and Business." We were honored to invite Sir Christopher Pissarides, Regius Professor of Economics at LSE and 2010 Nobel Laureate in Economics, to deliver a speech on evaluating the impact of AI on work and workers. He penned an essay exploring this issue, specifically crafted for this Dialogue, which he presented during the online event. We are pleased to share both his essay and the video of his speech.

How are workers in industrial countries affected by changes in work brought about by automation technologies, especially AI? What is their impact on productivity and growth? Can the situation be improved, and if so, how?

Although like many others engaged in research in the labour market, I believe that improving productivity is a paramount objective, I also believe that the wellbeing of workers should be a key objective as well. Higher productivity improves living standards and helps governments achieve their social objectives, such as good health and education systems and social support to vulnerable groups. But to get the higher productivity we need to work, and if work makes us unhappy, if it gives us depressions and mental illness, is that a price worth paying? I hope you will agree that the answer is that we should pursue the two objectives in parallel and improve wellbeing alongside productivity.

What is wellbeing? Wellbeing at work is simply the way that the worker feels about work. Are they happy doing whatever activity they are doing? Stressed? Relaxed? Sometimes objective measures, like medically diagnosed stress, mental illness, or absenteeism are used. But subjective measures, such as responses to questionnaires, are more encompassing and empirical studies are now using them more often. That’s the way that I will interpret wellbeing in this talk.

Changes in technology necessitate the transition of workers from one role (set of tasks) to another. They might also necessitate a job change, the closure of companies and the formation of new start-ups. “Role turnover” is more common than job turnover. But whatever the type, worker transitions take place continually. As a matter of routine, there is a lot of job creation and job destruction within sectors. The concern about automation technologies is this: the disruption is bigger than in the past, in terms of the new things that workers need to learn to make the transition.

Companies can do certain things to achieve smooth transitions and adapt to the new technologies. Making sure that their workers enjoy a good working environment and providing good training possibilities can ensure that the transitions are smooth and benefit the company as much as their workers.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is now driven by artificial intelligence. AI can have many more applications than previous technologies, being capable of influencing work at all levels except for the very top managerial level, where complex decisions need to be made. We don’t know precisely how much it is being used because it’s embodied in software that is not directly observed, unlike robots, which are self-propelled independent units. There is certainly a lot of hype – workers seem to live in fear of losing their jobs, and about 80% of employers say they are using it. But so far, the evidence shows that workers are not justified in their fears, and employers are using it in simple applications, like remote working or using cameras to watch remote parts of the office.

The general view is that the use of AI is still very limited, but we must prepare for it because it’s coming. In my view, more worrying than this, is that we don’t know in what form it’s coming, as we have a lot of choice how to develop it. So far, the news is not always good. In research that we did at the Institute for the Future of Work we found that in Britain many applications of AI have reduced the quality of work, at least as perceived by workers.

There are certain things that we know about AI, other than its potential, and these relate mainly to the enablers that countries need to have to take full advantage of it and develop it in socially beneficial ways.

To be able to make extensive use of AI countries need to have a strong digital infrastructure – powerful broadband, which is reliable, and universal. Their innovation capabilities need to be strong, with well-trained human capital to support them. They need to be open to collaborations and interact effectively with other similar countries. And they need to have good quality labour force institutions, including good social support to help workers’ transitions across jobs.

On these criteria, the US and China come out as top performers, partly because of their size and partly because of the emphasis and resources they have put into developing a good digital research environment. Europe is not as well prepared, but efforts are being made to improve the situation, as suggested by the recent (September 2024) Draghi Report on competitiveness. Compared with the big two, Europe is well prepared in one aspect of the transitions that will be necessary in the technological revolution that is coming, in the provision of social support and training facilities. In terms of wellbeing, or subjective happiness measures, Europe scores higher than other countries, most likely because of the social support and lower working hours that it offers.

Traditional AI, which carries out commands based on the data, is finding many applications, and it’s predictable where it’s going. Generative AI, which makes decisions and has much more capability to analyse data and language, can do many more tasks. Recent developments, which have reduced the computing capacity needed to execute it, are major advances in the application of gen AI. Large language models, such as Chat GPT, are ones that are threatening even professional jobs, such as paralegals, civil servants, and programmers. But it is not quite there yet. In a very interesting Luohan Academy lecture delivered only last week, Lindsey Raymond (in collaboration with Erik Brynjolfsson and Danielle Li) explained how Gen AI is benefiting less skilled workers more than the more highly skilled, probably because o far Gen AI is still learning from more highly skilled workers.

One thing that we can say with some confidence is that with AI we are unlikely to face a situation of job shortage across the economy. We are finding that AI is complementing work, not taking over jobs from workers. We should not be asking, where are the jobs going to come from in the world of AI, but what skills will I need to work effectively in this world?

It is easy to guess the general type of skills that will be in demand in the age of AI. Everyone will need to understand the basics of AI, as when computers were first introduced, when everyone needed to understand the basics of computing, such as messaging, file storage etc. For deeper specialisations, skills will be of two general kinds. They are new technology skills, for those that will be developing and applying the new technologies, and “soft” skills, for the larger number that will work on the provision of people-to-people services, possibly assisted by the new technologies.

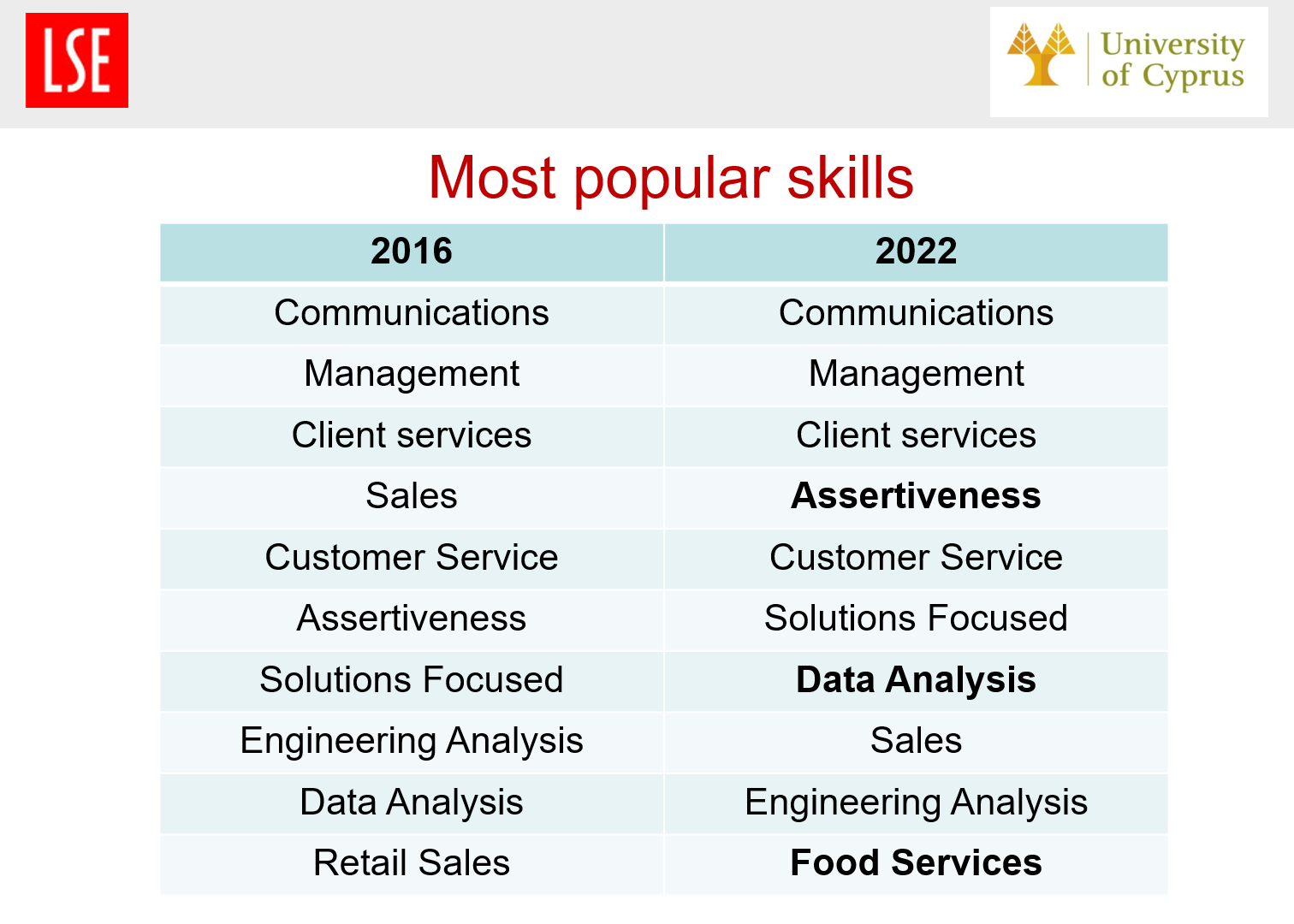

At CEP/IFOW we got all online job ads from Britain, about 2.5 million, and cleaned the data down to about 1.5 million per year. Firms advertise jobs with about 3,700 separate skills (on the Lightcast – formerly Burning Glass – definitions). We analysed in detail the skills required in 2016 and again the skills required in 2022. We find that “Old fashioned” skills dominate what employers want, in both years.

Although the top three skills demanded in each year are unchanging, and much more dominant than the ones below, new skills related to digital technologies are emerging. Recall that Britain during this period, like most other advanced countries, suffered from labour shortages. For the first time since vacancy records began, advertised job vacancies far exceeded job seekers. But although firms were looking for workers qualified to analyse data and do some technical tasks, most employers were looking for workers who were able to communicate clearly with both colleagues and customers, be confident in dealing with both, and support a good customer base; in other words, workers who were effective in person-to-person interaction.

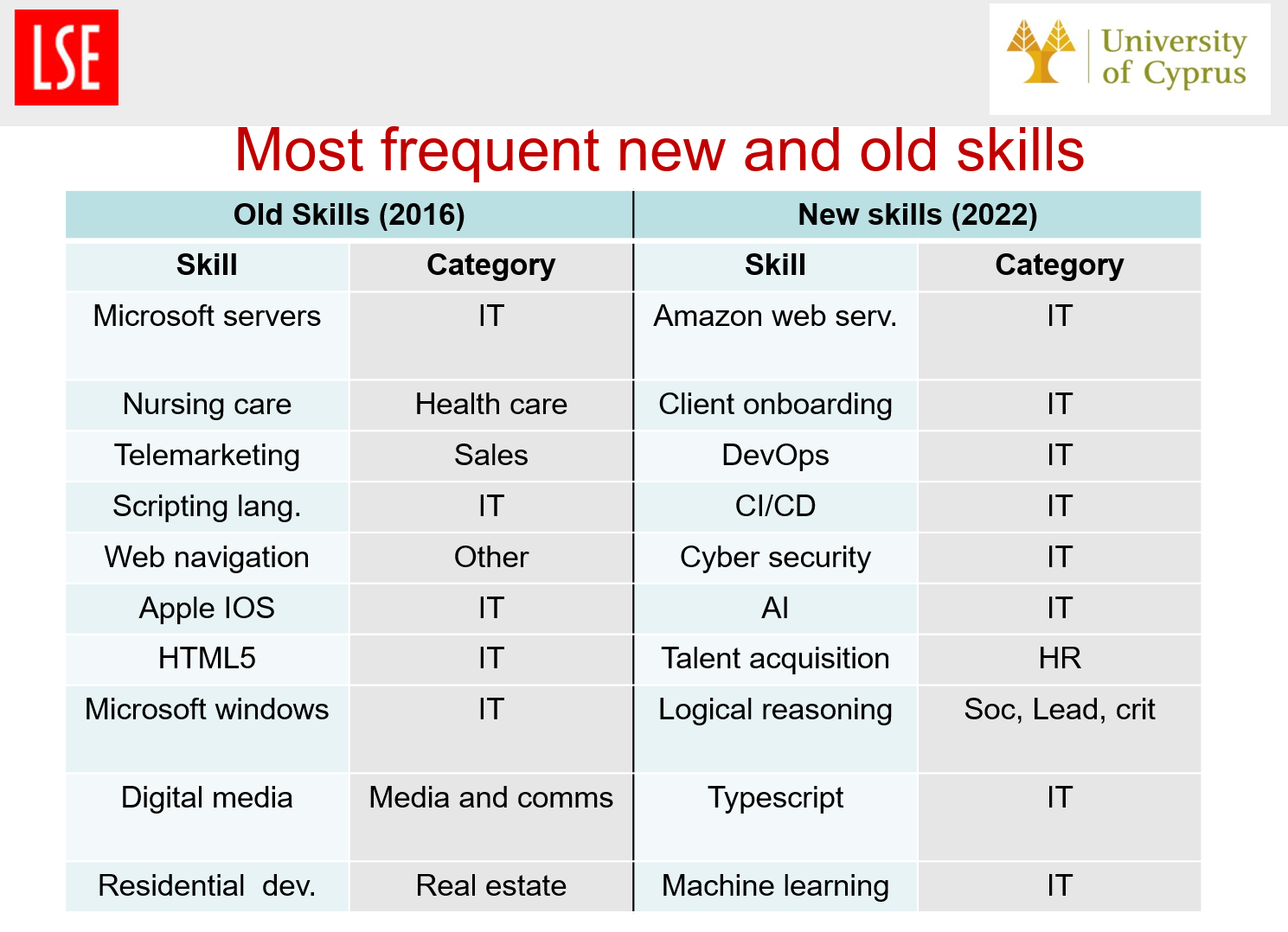

But IT-related skills are also emerging. Although the “soft” skills are mentioned in 80% of job adverts, and IT in only 40%, IT skills dominate when we look at the new skills that have emerged since 2016.

The biggest changes, both of new skills emerging and old ones disappearing, are in IT. There is a change in the IT tasks performed, the type of servers used, cybersecurity etc. Dealing with people ranks high even in the IT sector – as in onboarding and talent acquisition, which, although listed under human resources, uses a lot of IT information.

IT is followed by Health services and then Engineering. These are also sectors which are experiencing high demand for labour and changing skill requirements.

With changing skill needs, firms need to spend resources on training. Government has a role to play here, subsidising training, especially for smaller firms. Changes are also required in secondary education, as the older methods of teaching are not well suited in the new world of fast changing technologies.

Should one train in STEM? The answer to this question might be obvious but there are some subtleties involved. I would say Yes, up to some basic knowledge – but don’t be misled that that’s where the future of human work is! Many STEM related tasks can be done by AI and as the use of AI is expanding, fewer STEM trained professionals will be needed. AI is not good at offering person-to-person services in non-technical sectors of the economy, and that’s where human labour will always be wanted. Especially in our ageing societies. AI machines might be good at diagnosing health problems and even performing operations, but their capabilities do not even get close to humans in providing care and support for older people.

The challenge for these person-to-person service jobs is how to make them attractive for large numbers of workers, especially new entrants to the labour market. These sectors are predominantly labour-intensive and low productivity growth sectors, so they need to be supported by the rest of the economy. The problem is aggravated by the fact that in countries like Britain and other European countries, the public sector plays a big role as employer. The problem is especially acute in National Health Services, which are facing increased pressures because of ageing populations.

I have focused on the impact of AI on jobs and in the changes that it is bringing to labour markets. What about productivity growth? Are we on the threshold of a major productivity boom? Some believe that AI will have the capacity to increase productivity substantially. Personally, I doubt whether it will make much difference to the productivity statistics, although it should improve the quality of services that we get and reduce mistakes. This is very much like the impact that computers and software, such as Microsoft Office had, in the early days of digitalisation. You may have heard Robert Solow’s famous quip at the time, that you see computers everywhere except in the productivity statistics. I think something similar will be experienced with AI, for as long as we have no way of measuring quality and speed of service provision in our national statistics. Or even more broadly, because we have not yet found ways of measuring wellbeing in our GDP statistics.

It is clear from the discussion so far that both workers and their employers are facing big challenges. There are a lot of uncertainties about the future and about the best approaches to work. How are workers coping?

Surveys of workers’ attitudes to work have proliferated recently, as part of life “happiness” surveys. They find that losing your job is one of the life events that gives most unhappiness (along with illness/death in the family and divorce). But being at work is one of the activities that gives most stress and dissatisfaction, especially some things associated with work, like commuting or seeing your boss. Only being sick in bed scores consistently below being at work (Bryson and MacKerron, 2017, De Neve-Layard book, 2023)

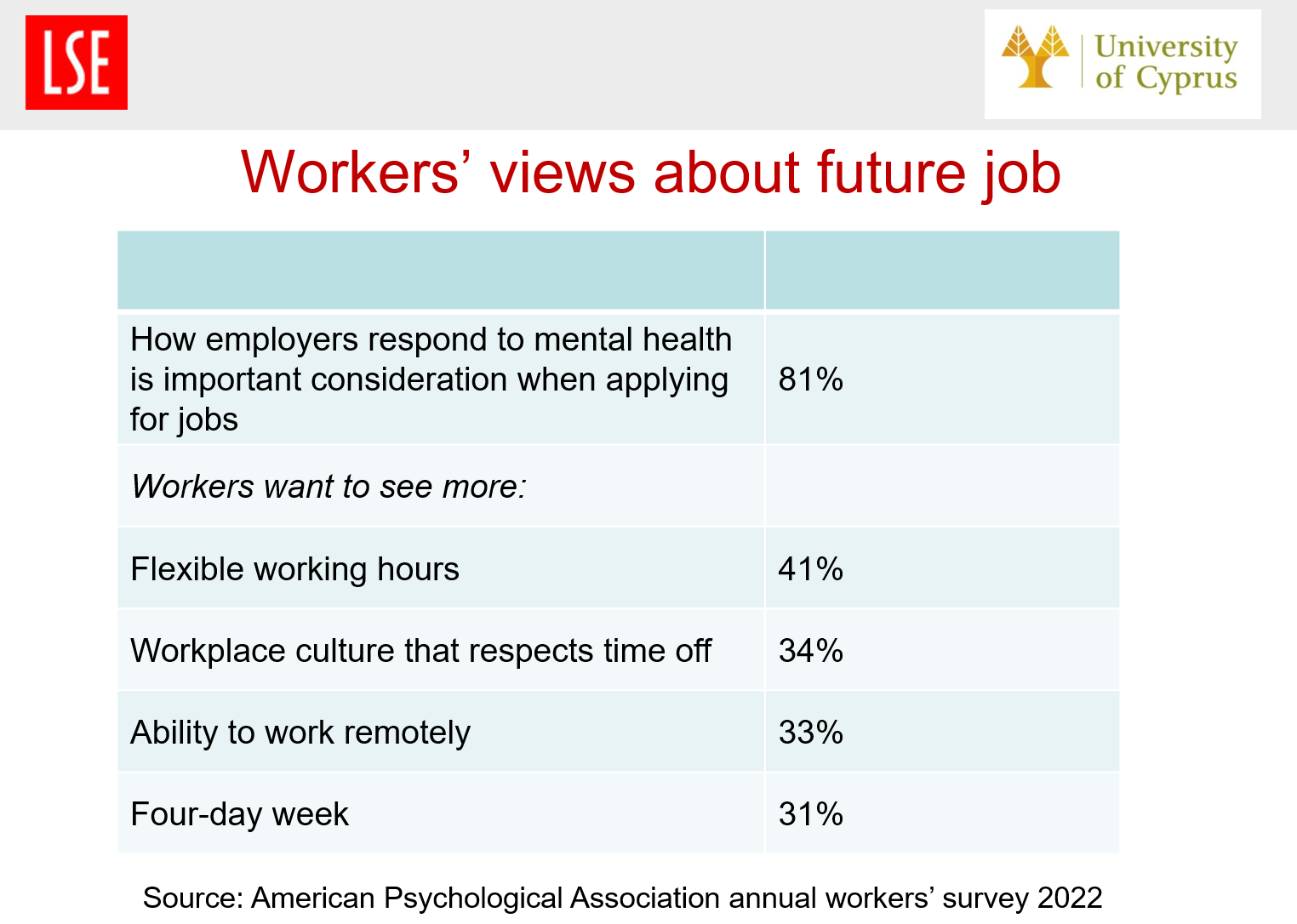

One might ask - isn't that what the economist should expect? No one should feel happier working than pursuing leisure activities off work, otherwise there would be no reason to pay people to work. But there is room for improvement. When workers are asked about what would make them feel better at work, they mention better communication with managers, more transparency in the company’s activities and plans for the future, better social relations at work, more time flexibility and more autonomy in choosing their role in the organisation. More money comes low in the list. There are also variations across workers. For example, professional people feel better at work than non-professionals.

Recent automation technologies seem to be making things worse. Studies of connections between the risk of automation, measured, e.g., as in Frey-Osborne, and subjective wellbeing find negative corelations (Clarke and Rohenkohl, IFOW, 2023). Workers in jobs that run a higher risk of automation express less job satisfaction than those in safer jobs. Clearly, worker wellbeing could be improved without violating what economists call the work/leisure trade off.

In other work at IFOW, based on interviews with workers, we found that some technologies improve wellbeing at work, others make it worse. For example, the use of laptops, tablets, smartphones and real-time messaging tools – are associated with an improved quality of life for workers. Workers also feel that they have more flexibility and autonomy at work. But technologies associated with AI, surveillance or automation increase anxieties, partly because of fear of job loss, but also because some good features of traditional types of work, such as enjoying uninterrupted free time away from the office, might be lost.

Flexibility in the choice of hours by the worker is another frequently mentioned feature of good work. Several empirical studies of wellbeing at work, (e.g., summarised by De Neve and Layard, 2023, chapter 12, IFOW Good Work Monitor), concluded that having choice over hours is positively associated with worker wellbeing. This feature of good work has become more important since the pandemic. The new technologies that developed during the pandemic to facilitate remote working (zoom, teams, etc.) certainly help, but also, once home working was forced on companies, most discovered that flexible working time might even improve productivity, not only worker wellbeing.

More recently the four-day week is becoming more popular as a way of reducing hours. Even in America there is evidence that there is increasing demand for fewer hours of work. The American Psychological Association in its annual survey last year asked workers what would make a future employer attractive to them. The things they emphasised are related to time flexibility, including working from home or working four days a week.

I conclude with the main message. This is that the new technologies based on AI can improve the quality of work, productivity (although not very much) and worker wellbeing, but only if they are applied responsibly – and both government and companies have a role to play in this development.